This article is based on experience over 5 years of developing a Creativity Programme in two Secondary Schools in Ireland. The end result is a Creativity Book (developed in both electronic and hardcopy). Weblinks to these ebooks are given below.

I welcome ideas and suggestions from other school communities on how to adapt and develop our creativity programme. Please email me on paulmartinwriter@gmail.com

Background

Human creativity distinguishes us from AI. It develops self-expression so important for social skills and well-being. It facilitates new perspectives, so important in problem-solving in every workplace (including those based on apprenticeships) and in every walk of life. It’s important to show students that creativity is not “just for the clever, arty people”. Creativity, whatever its form, just makes life better and more enjoyable.

My idea for a school Creativity Book began in 2021 during Covid. My focus was to support mental health by enabling students to give voice to their thoughts and feelings during this difficult time of isolation. The format was kept simple. A book of student poems accompanied by web-sourced images in ebook format for easy social media distribution.

Over the next five years this format progressed to a Creativity Book in both print and electronic versions. All poetry and art content is produced exclusively by students (short stories rarely stand out and seem not best suited to format). The only non-student content exception is a “My Favourite Creation” section where two teachers from diverse subjects describe their own favourite written, visual, musical or physical creation.

6 lessons – Developing a School Creativity Book Programme.

1. Establish a creativity culture (Target first years)

Experience has shown that the best target groups for the Creativity Book are first years (aged 12/13) followed by 4th Year/Transition Year (aged 15-17). Third, fifth and sixth years are focused on academic studies. Second years are often more self-conscious and “cooler” than first years meaning they are less inclined to stand out from the crowd and express their personal experiences.

Honing in on students entering the school also signals that creativity is highly valued and central to “our school” and the secondary school experience. It’s “what we do” and helps to embed a creativity mindset in students for their following 6 years of school. The prestige given to creativity is reinforced through the year/end Creativity awards presented at the annual prize event.

Linking in so actively with 1st Years facilitates re-engagement with students in any year but especially in Transition Year. Students by then know the process and the relevant teachers and regularly submit, or are encouraged to submit, writing or art content towards the Creativity Book.

2. Enable students of all ability to participate (Recognise the doodlers!)

How can students with literacy or learning challenges be fully supported to contribute to a creativity book? Just look at their copybooks! Many students – some with literacy issues, some without – do wonderfully artistic doodles and drawings in their class copybooks. So give them free rein

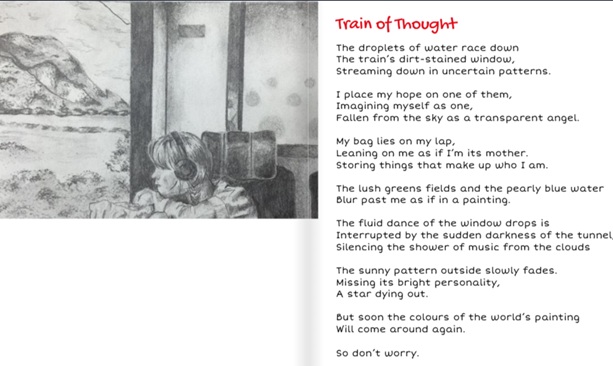

We invite student to submit written and/or artistic work. This idea was inspired by both this doodling and the poet Paul Durcan’s 1987 book “Crazy about Women”. In this, he wrote poems inspired by paintings in the National Gallery in Dublin. The poem and painting were reproduced side-by-side in the finished book.

So we decided to simply reverse the process. Ask students to write a poem and then engage students in art class to produce a visual image inspired by it. This led to the participation of many more often less confident students – for example, those with dyslexia, or who might view themselves as of lower academic achievement.

This one change, in the third year of the programme, opened doors to expression for many more students, increased creativity content 50% (all the art work is theirs) and resulted in a highly visually appealing book being produced.

3. It’s teamwork, not a solo run (Share the credit)

Just as the content is all about students, the book will only happen with the buy-in of many busy teachers. So make it as easy as possible to engage with by sharing templates and examples (see point 4 below). Say thanks. Mean it. And keep saying it. Recognise their essential work in the book’s introductions.

4. Get them started with ideas (Share possible topics)

So how does a teacher help a student to write a poem if they’ve never done it before? Start with listing possible topics connected to their own lives, for example:

- Sports/Activities: soccer, rugby, GAA, horse- or bike-riding, skateboarding, video-gaming etc

- Animals: Dogs, cats, crab, horse, bees, foxes, fish

- People close to them: Parent, sibling, grandparent (occasionally one passed away), friend

- Seasons/events: Summer, Christmas, Autumn, Halloween

- Family home countries: Challenge students, especially those with origins outside the country, to write about summer visits to family and places abroad.

- Places: Mountains, beaches, hometown, school, bedroom

Then reveal the supermodels! Show them poems written by students in previous years. Students enjoy recognising names of older siblings and students as the ebook is displayed on screen. It makes creativity just normal. What’s so strange or daunting about writing a poem if those older students in my neighbourhood did it? Well, so can I!

5. Gather sufficient quality content (Be a magpie)

Creativity doesn’t just happen in the formal class setting. You might struggle to find enough suitable art pieces to accompany a poem, or vice versa. So be a magpie.

It’s impossible to try to bring together all the creativity happening in any school. But you should always have alert antennae for so many of rich pickings available in every corridor, class and canteen area. Short of an image for a certain poem? Ask a student you know interested in art and might use other forms e.g. computer art design.

Some creative pieces have entered our books through odd channels. A vivid description of a pizza slice passing through the human digestive system was first written for a science class. An under-the-radar “artist” was spotted notebook doodling in the canteen. Earwigging in the staffroom unearthed a winning art piece originally produced for a history local-heritage project. Other pieces were spotted from exhibitions posted in the library, art classes and school corridors.

6. Don’t crash on launch (Promote and promote again).

Many students and teachers put huge work goes into the Creativity book. Don’t let it die a death as a one-day (school announcement) wonder. Use Social Media post-launch to keep it front and centre over several weeks. Share a “Poem of the Week” (with accompanying image(s) throughout April and May on school social media. (See Apr-May in the timeline below). Chose that week’s poem/art piece to connect with the calendar e.g. a summer poem when the weather is nice, a sports poem if there is a big school cup match, a travel/foreign poem if the school just back from mid-term etc. You don’t need to promote a “weekly poem” every week but 4-6 can easily be should in the final two months of school.

Timeline

Remember the golden rule of project management. Work backwards! If you want the book concluded, as I do, by St Patrick’s Day (March 17th) what actions need to happen before then. My rule of thumb is:

- Oct, week 1: email all relevant English teachers (1st yrs classes) with support material (links to past creativity books, PPT with poetry/art examples, one page jpeg explaining “competition/challenge” for teachers to post on class Teams or Google page). Set mid December deadline for poem writing.

- Mid November: Remind/prompt English teachers “casually” in the staffroom. Follow up with email.

- Early December: Send reminder email to English teachers, if required.

- December: Engage with individual teachers to ensure students type up poems selected from original submissions.

- Early Jan: Share and discuss selected typed poems with lead teacher in Art Department

- Jan/Feb: Begin drafting and formatting the book. (I use bookcreator.com). Continue to engage with art department for appropriate images to accompany poems.

- Feb: Draft Principal’s Introduction/request Principal’s Introduction for Mar 10th deadline

- Mar: Gather and chase all materials. Complete ebook in advanced draft.

- Mar/Apr: Depending on Easter date, launch ebook through school social media and English 1st year tutor groups two weeks before Easter. Request quotations for hardcopy printing. Select printer. Send proofs to printer

- Apr-May: Distribute hardcopy book to every student selected for inclusion in book. On school social media share Poems of the Week with accompanying image(s). Connect these poems with the weather (e.g. summer poem), national or school events (e.g. sports successes). A poem is not necessary every week. But 4-6 should be shared.

- May: Present Creativity Awards at year end school presentation day for Poetry and Art.

Links to School Creativity ebooks

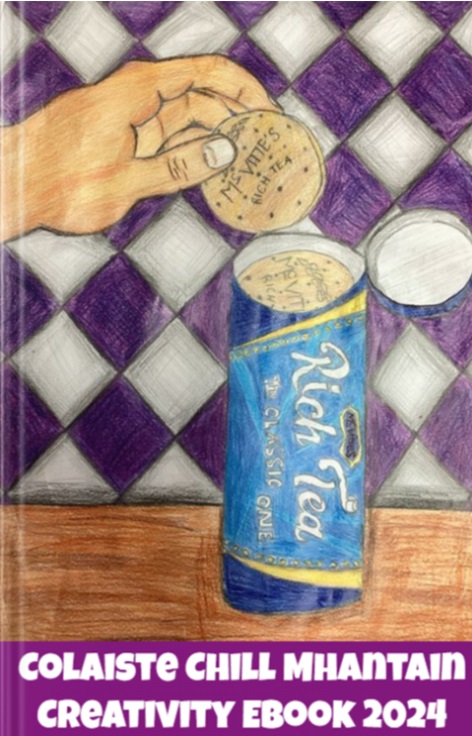

Coláiste Chill Mhantáin Creativity Book 2025

Coláiste Chill Mhantáin Creativity Book 2024

Coláiste Chill Mhantáin Creativity Book 2023

Ass. Prof. Eric Haywood (with author) in the UCD School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics.

Ass. Prof. Eric Haywood (with author) in the UCD School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics.